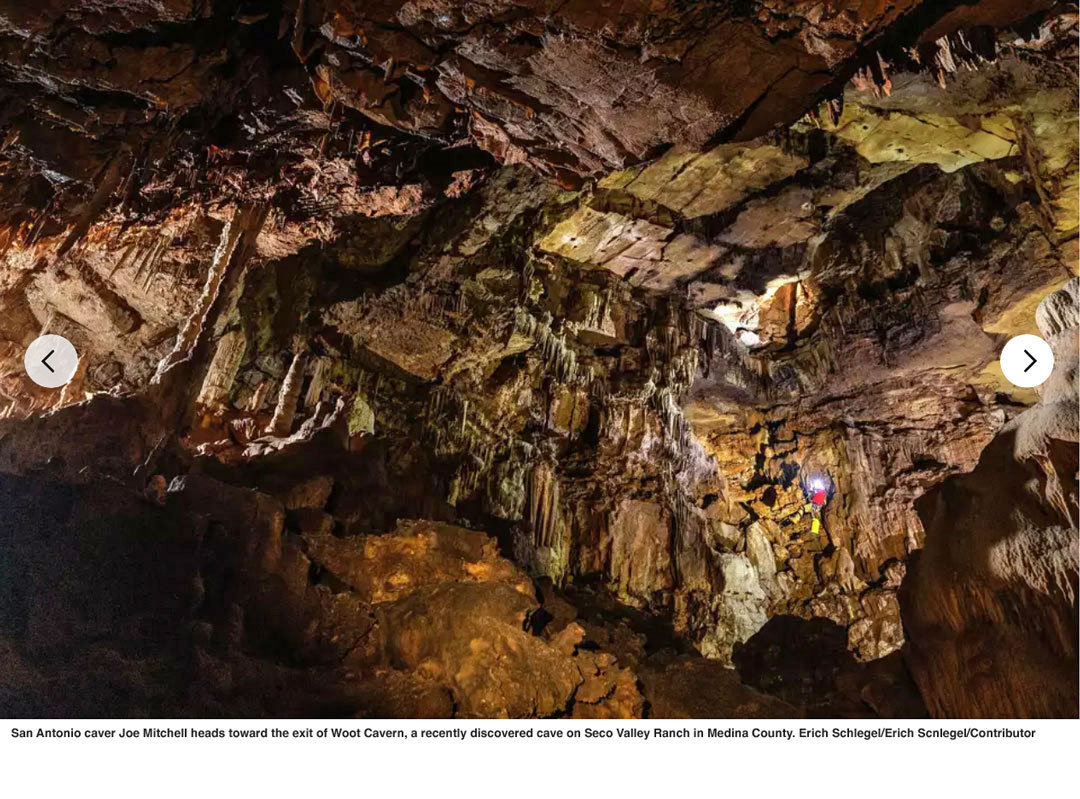

"Like walking on the moon': Conservation deal helps uncover rare Hill Country cave The city of San Antonio's deal with a Medina County family was intended to protect the aquifer. But it led to the discovery of a spectacular underground bonus."

By Liz Teitz, Staff writerOct 4, 2024

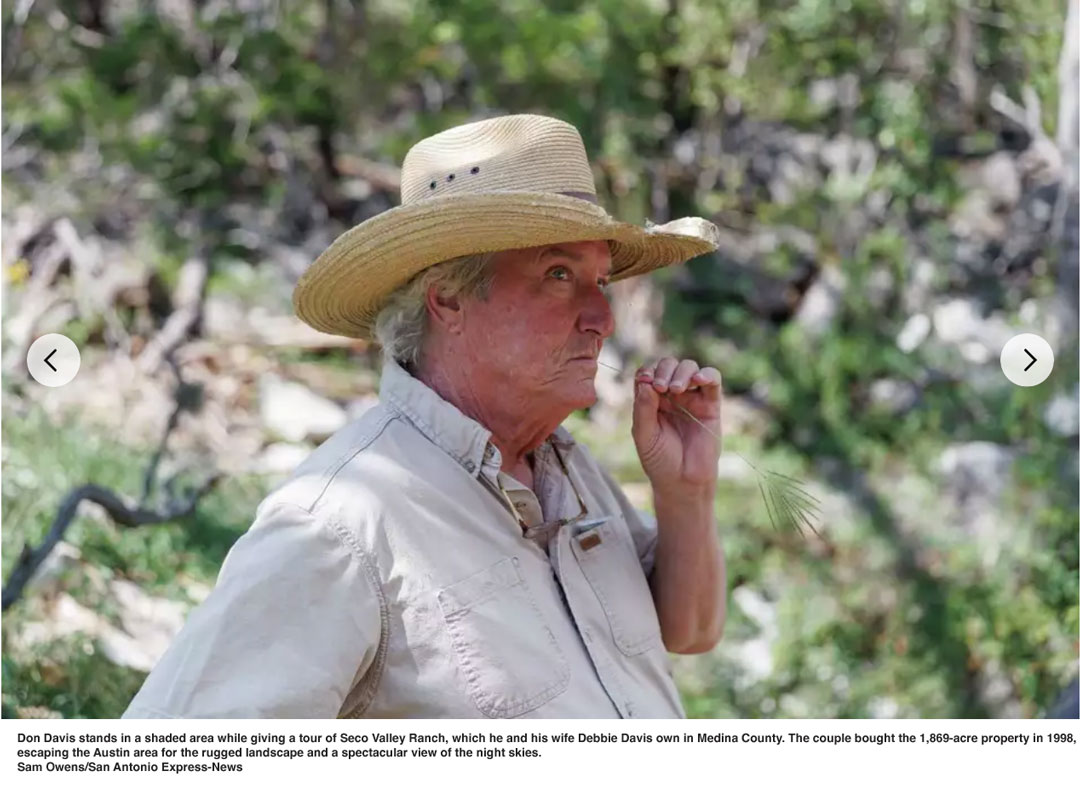

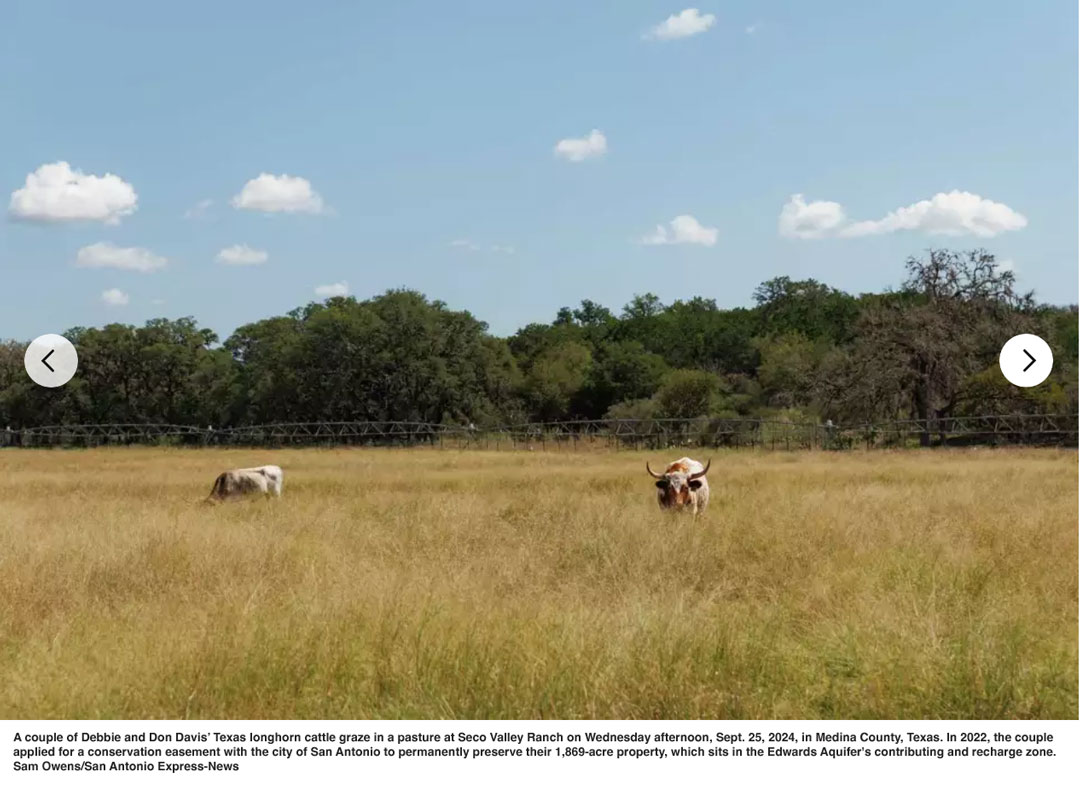

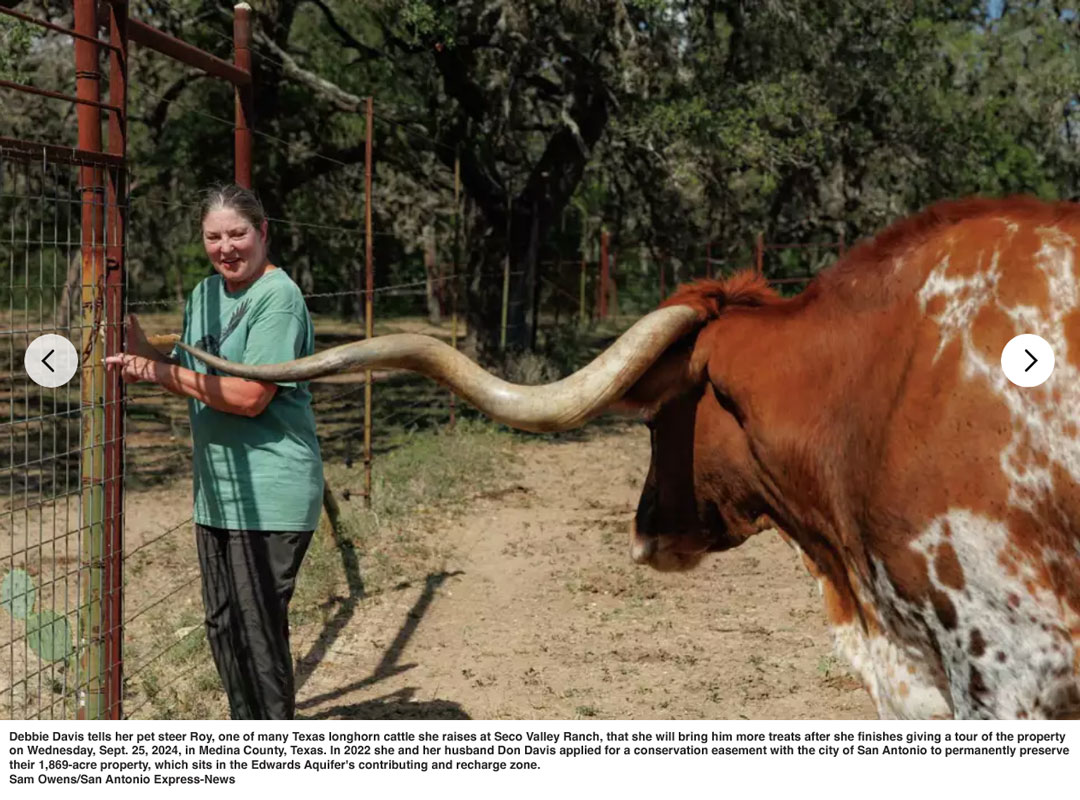

MEDINA COUNTY--When Don and Debbie Davis bought Seco Valley Ranch in 1998, they loved the remote and rugged land, the creeks that ran through it and the spectacular view of the night skies, unmarred by light pollution.

It was brushy in some areas, over-grazed in others and wild everywhere: riding across it on horseback for the first time, “you didn’t know if you were going to come up to a mountain lion,” Debbie said.

A few years ago, they started making plans to permanently preserve the 1,869-acre property in its current form through a conservation easement with the city of San Antonio. The deal would ban most development on the land — which is in northwest Medina County, about a 90-minute drive from central San Antonio — and ensure it continued letting water into the Edwards Aquifer below the ground. The ranch sits in the aquifer’s recharge and contributing zone, where water enters the groundwater system.

That process required a geological assessment by the Edwards Aquifer Authority, and in 2022 that assessment revealed a hidden sinkhole on the property and a portal to more secrets underground.

READ MORE: Conservation deal will ban development on 1,200-acre Comal property

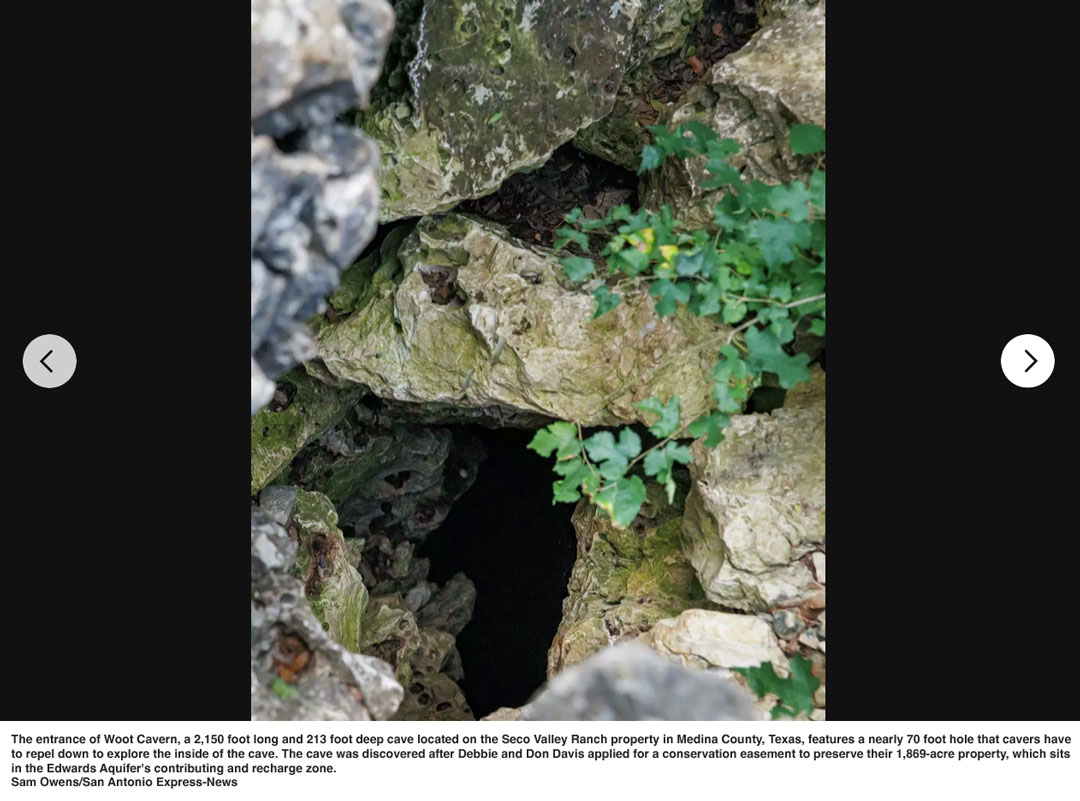

Standing in the sinkhole, a rocky depression tucked away behind brush and trees, Debbie tied a rock to a rope and lowered it inside the opening. More than 70 feet later, it finally struck something, she said.

The Davises later learned their property included a spectacular cave more than 200 feet deep, filled with unique rock formations, salamanders and winding paths to explore. That cave and others on the property are now protected under the same easement that will conserve the Hill Country landscape above it.

While the agreement is aimed solely at protecting aquifer recharge, it’s come with an unexpected bonus: the discovery and conservation of new parts of an underground world.

Aquifer protection

The Edwards Aquifer is an underground cavern system that’s a vital water source for Central Texas. It provides half of the San Antonio Water System’s supply, and more than 2 million people rely on it.

The system is recharged by surface water entering through karst features, which are fractures in the surface such as sinkholes and caves. Water moves from the contributing zone, a large expanse to the north and west of San Antonio, into the recharge zone, a strip of land that runs from Uvalde County through northern San Antonio and into Hays County, where the fractures allow the water to enter. The two zones combine to form a watershed that covers more than 2.5 million acres, according to the Edwards Aquifer Authority, which manages the system.

Impervious cover — surfaces like pavement, sidewalks and roof shingles that don’t allow water to pass through — can alter runoff flows and prevent water from seeping into the ground. The recharge zone is also sensitive to pollution, because any contaminants on the surface can easily enter the aquifer, affecting water quality.

Since 2000, the city of San Antonio has worked to preserve land in the recharge zone by purchasing property or paying for easements, which are agreements that limit how land can be used.

In 24 years, the Edwards Aquifer Protection Program has spent more than $260 million and protected just over 184,000 acres, primarily in the recharge zone, as well as a small portion in the contributing zone.

“That is the one and only thing that we’re looking at,” said Francine Romero, who chairs the city's Conservation Advisory Board that considers the agreements and decides whether to recommend them for City Council approval.

“We don’t get into whether this property’s so pretty or historic or it’s endangered species habitat,” she said. The program’s only mission is to protect land in the two aquifer zones, because doing so helps protect the city’s water supply.

READ MORE: Who is ‘Edwards,’ anyway? 5 things to know about the Edwards Aquifer.

From 2000 through 2020, the program was funded through a voter-approved sales tax. In 2020, the San Antonio City Council voted not to renew that and to instead fund the program by issuing debt and using money from annual transfers from the San Antonio Water System, the city-owned water utility. SAWS transfers 4% of its operating revenues to the city each year; in 2025 that’s projected to be about $234 million, according to budget documents.

Two nonprofit partners, the Nature Conservancy and Green Spaces Alliance of South Texas, work with interested landowners who want to pursue the program. They bring potential properties to the board and work with appraisers to assess their value.

Easements typically reduce a property’s value, because the limitations on how the land can be used make it less valuable on the market, so the city program pays for the difference, essentially covering the cost of devaluing the land.

In the case of the Davis family's Seco Valley Ranch, the restrictions reduce the market value about thirty percent, so the city paid about one third of the current estimated market value for the easement.

Amounts vary depending on the property. For a tract that’s considered favorable for development — if it has more road frontage or less slope, for example — the financial impact would be larger, so the easements tend to be more expensive.

“If you have a property that’s really valuable, we sometimes have to pay maybe 50% to 60% to put an easement on it,” Romero said. The Davises' property was “on the low end” at about 30%.

In addition to the appraisals, the process includes a geologic assessment for prospective properties, done by the Edwards Aquifer Authority, before the easement is brought to the board for approval.

'There was no bottom'

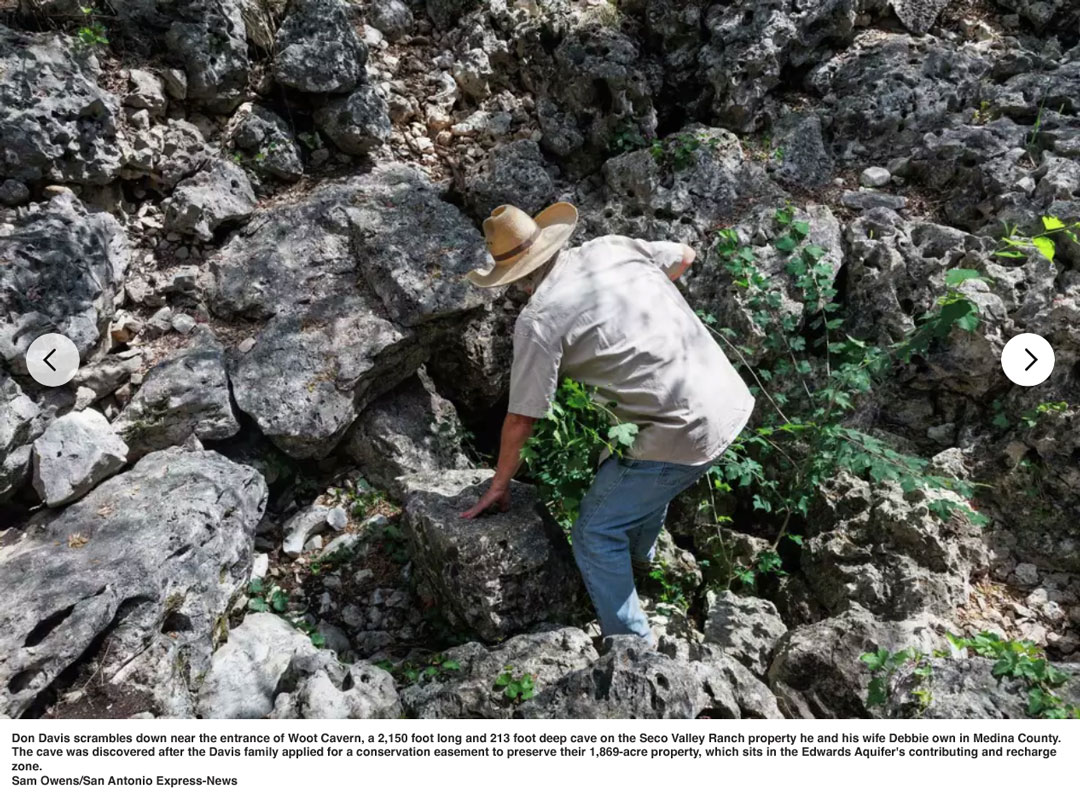

In 2022, when the assessment process got underway at Seco Valley Ranch, the Davises already knew about one cave on the property.

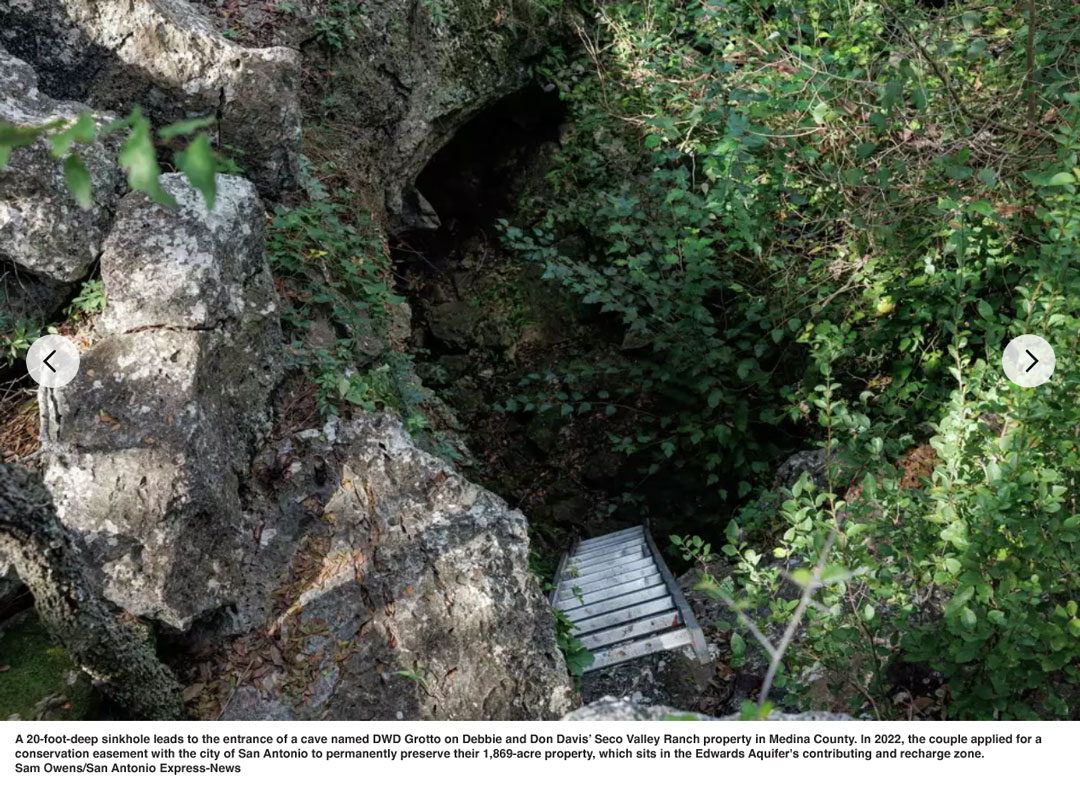

Don had been giving a tour of the ranch to an official with the Audubon Society’s conservation ranching program, and made a stop at a 20-foot-deep sinkhole.

“He started moving rocks around, found a hole and crawled through it,” where he was able to see a room underground, Don said.

They started looking for someone to explore and contacted the Bexar Grotto, a San Antonio-based caving organization. A group of cavers came out to explore, and found what’s now known as DWD Grotto, a cave accessed though an opening so small that “you’ve got to crawl on your belly like a reptile” to enter, Don said.

He and Debbie had known about that sinkhole for years, and knew it was likely a recharge feature. The cave and its exact connection to the aquifer are still being explored.

READ MORE: How to get farmers to use less Edwards Aquifer water? Pay them.

But the aquifer authority’s assessment showed another depression, a dark spot on a terrain map. Don and Debbie took the GPS coordinates and went to the spot, where they found the sinkhole that revealed the second cave.

They called the Bexar Grotto again, whose members returned to explore.

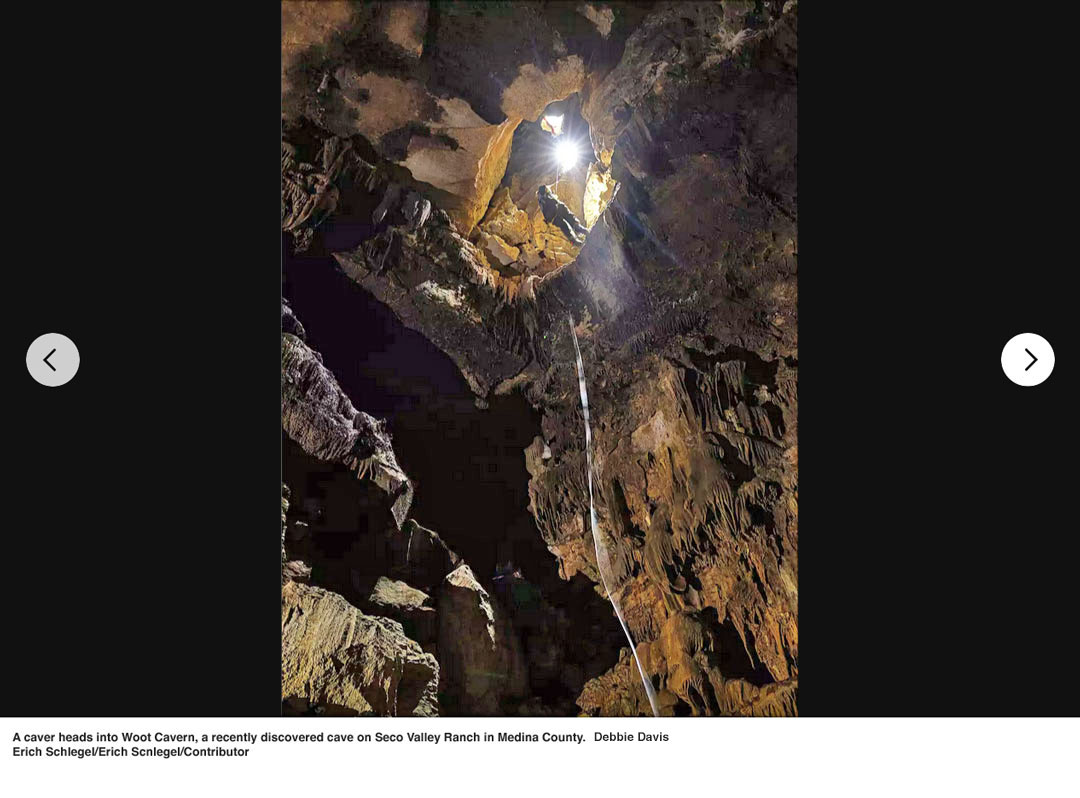

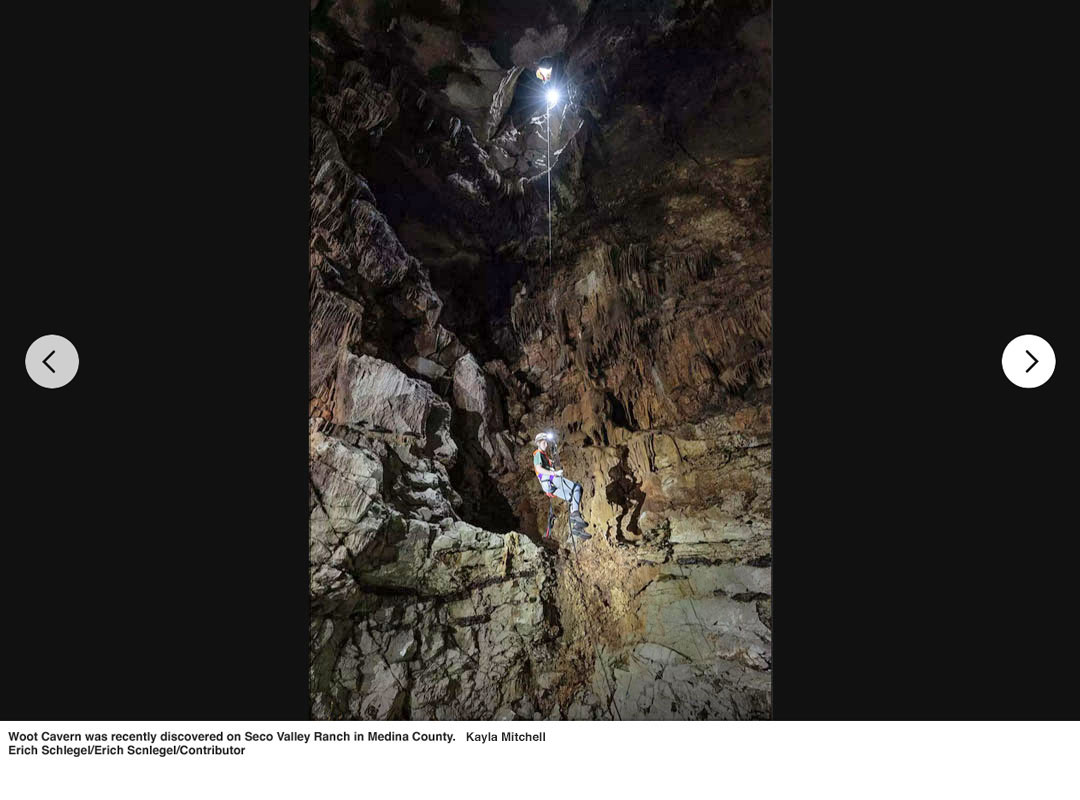

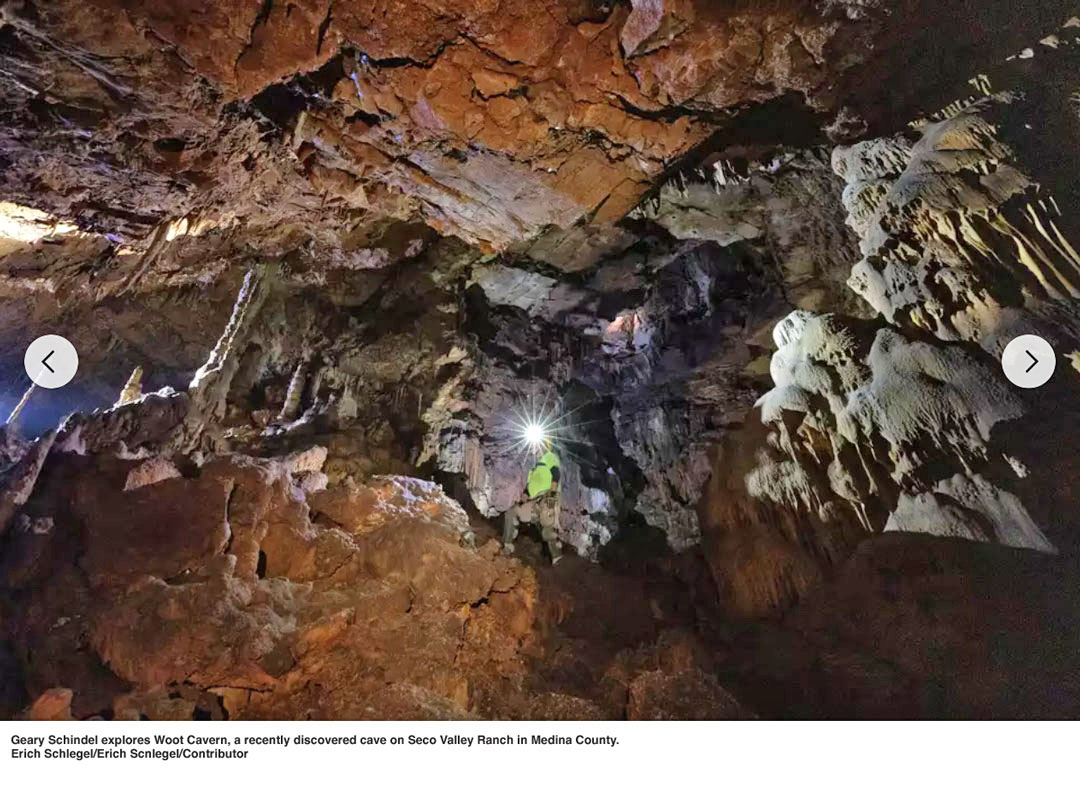

“We shined a light in there and normally you’d see a rock wall,” cave photographer Bennett Lee said. “There was no bottom.”

He and fellow member Matthew Taylor chipped away at the rocks to widen the entrance until they were able to squeeze themselves inside. Lee lowered himself underground first.

“As soon as I got past the initial lip, I saw a huge room,” Lee said. That’s unusual; often, exploring caves reported by ranchers doesn’t pan out, or cavers find only small burrows and caverns. To find a cage this large that was previously unknown is rare, he said.

“To find a room that big, with formations like that, really doesn’t happen a lot in Central Texas,” he said.

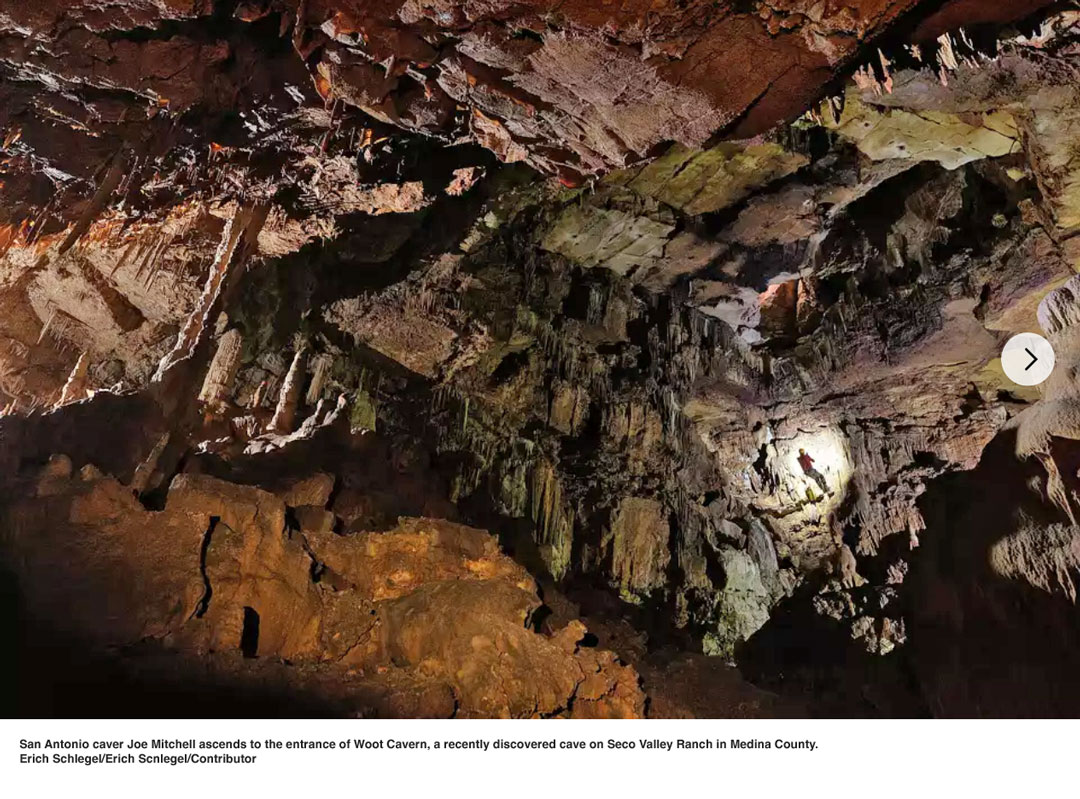

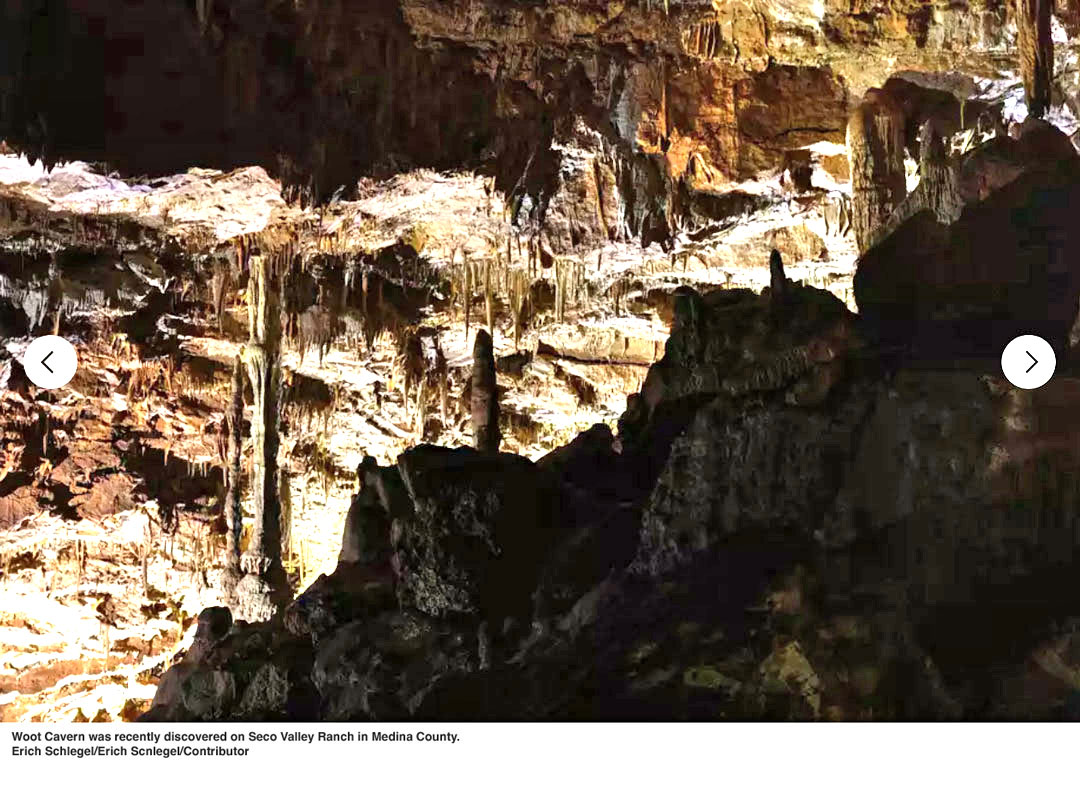

The cave, now known as Woot Cavern, named for Don’s great-uncle, has been surveyed nine times, according to the Texas Cave Management Association, a nonprofit organization that works to protect caves and promote cave research and education.

At 2,150 feet long and 213 feet deep, it’s the state’s 69th longest cave and 30th deepest cave, tied with Frio Queen Cave in Uvalde County, according to Joe Ranzau, president of the Texas Cave Management Association. Woot Cavern is almost as deep as Natural Bridge Caverns in Comal County, though that popular

attraction is almost nine times longer, according to data from the Texas Speleogical Survey.

After hearing descriptions of the cave from Lee and Taylor, the Davises wanted to see it with their own eyes. They spent five months training with the Bexar Grotto in San Antonio so they could enter Woot Cavern themselves.

The cave is dark, lit only by headlamps. Inside, sound echoes off the walls, and creatures like blind salamanders and isopods, a type of crustacean, make their homes. On one descent into the cave, Debbie said, a caver found a snake that had fallen into the opening, and carefully transported it back to the surface.

“It’s totally silent,” Lee said, aside from echoes and the occasional sound of dripping water. The main room in Woot Cavern “smelled like crisp, clean dirt,” he said.

On return trips, cavers have surveyed the main room and passages leading away from it, including three more rooms, Don said. The next frontier to explore is a

“sump,” a passage filled with water that will require cave divers and an underwater drone to investigate.

There’s potentially a third cave on the property, too, which ranch foreman James Sanchez found in a third sinkhole.

Cavers crawled inside the narrow passage, but had to turn back because of “bad air,” Don said, or a buildup of carbon dioxide. They’re planning to return and try again.

'Like walking on the moon'

Woot Cavern is a significant cave for the area, Ranzau said, both for its size and the visible water moving through it, indicating a direct connection to the Edwards Aquifer.

Caves are just one type of karst feature that allows recharge, said Mark Hamilton, the Edwards Aquifer Authority’s executive director of aquifer management services. While they might look more impressive than small sinkholes in streambeds, for example, that doesn’t necessarily mean they always provide more recharge.

But caves are “a grand indicator of super-sensitive environments,” he said, “and under the right conditions, they would certainly offer opportunities for rapid water flow through them.”

That’s not to say they aren’t important, he said — just that the entire recharge zone and all its fractures are crucial to the groundwater system, from the barely visible sinkholes to the show-stopping caves, like Woot.

“Karst features, they’re all important,” Hamilton said. Caves offer other benefits, he said, as they hold “a record of the past.”

“They take hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of years to form,” Lee said. Stepping inside a virgin cave where no one has been before, like Woot Cavern, is like "walking on the moon," he said.

“We know we’re the first people to set foot on that soil,” he said. “That’s the dream of all cavers.”

They’re also fragile, both in terms of the geology inside and the ecosystems within caves. Animals inside certain caves may be completely isolated, making them unique from other, similar species, Lee said.

Central Texas is home to endangered and ancient species that exist nowhere else on the planet, Ranzau said, some of which, like the caves and formations, are ancient.

The slightest change in the environment, such as moisture, water level or exposure to pollutants, for example, can disrupt cave ecosystems and affect the formations and creatures inside, Lee said.

The cave management association, which is made up of volunteers, works to protect and conserve caves in Texas, where many have been damaged or destroyed by development over the years.

“Urban encroachment is our No.1 challenge,” Ranzau said, pointing to illegal dumping, incursions from sewer lines and trespassing.

That means even though the city’s easement on Seco Valley Ranch is aimed at prioritizing recharge, it will also benefit the caves, preventing them from being paved over, closed up or threatened by nearby development.

The Davises are also working with the cave management association on an agreement that will ensure access to the caves to allow for further research, and ensure the caving organization remains involved.

“The landowners thought it was very important to continue the exploration aspect, both in the caves and on the ground,” Ranzau said, so an access easement will codify that in perpetuity and allow the organization to be involved in managing the property.

“The intent is to continue finding and exploring,” Ranzau said.

“The long-term goal is that Woot is taken care of,” said Clay Thompson, Green Spaces Alliance’s director of conservation and stewardship. He has been working on the effort with the Davises for several years.

That agreement is still in the works, in part because it’s an unusual situation, Ranzau said.

“It isn’t something that’s boilerplate. There are not a lot of cave and karst access and management agreements out there in perpetuity,” he said.

Once it’s completed, the easement will run alongside the city’s easement, ultimately preserving both the open space for aquifer recharge and the underground worlds for exploration and study.

That’s valuable because of the rarity of caves like Woot Cavern, Lee said.

“We know of so few of these,” he said. “So the ones that we do know, it’s great to preserve them for future generations.”

Oct 4, 2024

LIZ TEITZ

Reporter

Liz Teitz covers environmental news and the Hill Country for the San Antonio Express-News. She writes about the San Antonio Water System, news in New Braunfels and Comal County and water issues around Central Texas. She can be reached at liz.teitz@express-news.net.

Liz joined the Express-News in June 2023. She has been a reporter for eight years, covering housing, government, education and other topics for the Ouray County Plaindealer, Hearst Connecticut Media Group and the Beaumont Enterprise. Liz grew up in Rhode Island and graduated from Georgetown University.